At a recent training presentation, I challenged the audience to reconsider the way they perceived training and its impact their fitness. To illustrate my point, I drew a simple chart like the one below to represent how I believe the vast majority of people consider fitness. Let’s call it the Linear Perception of Performance. Fancy name for a simple graph, but stay with me.

Graph 1. The Linear Perception of Performance.

Here, the Y axis is an arbitrary level of fitness. The X axis is training volume or training load (training load = training volume x intensity). The red line represents the relationship between the two.

In most people’s minds, becoming fitter is simply a matter of training more. Train for X hours and become Y fit. Train for 2X hours and become 2Y fit. It is easy to extrapolate this perception and see how it can lead to excessive training, especially in a sport like cycling where kilometres per week are worn like a badge of honour.

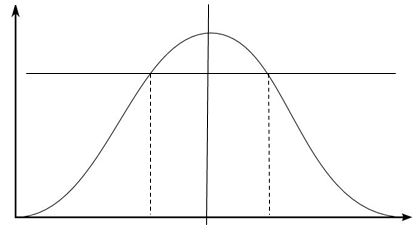

But there is an alternate view, and one that I believe is much closer to the reality of performance. Let’s call it the Bell Curve Perception of Performance. I know, but stay with me.

Graph 2. The Bell Curve Perception of Fitness

In this model, the relationship between training volume and fitness is not linear, but takes on the shape of a bell curve. Like the first graph, it can be seen that fitness increases with training, but only to a certain point, beyond which it starts to decline. This should not be a surprise as we are all aware of the concept of overtraining.

However, the two solid lines that intersect the curve convey two important ideas. Firstly, the centre vertical line implies that there is an ideal point at which training volume or load is most effective and fitness is maximized. This point may be eight hours or ten hours per week, or if you train with power, it may be 500 or 800 TSS points per week. The key concept to take on board is that it is possible to train beyond a point that maximises your performance. The actual point for each individual may be elusive, but it is important to consider the concept that you may in fact perform better with less training than you are currently doing.

Second, the dotted lines either side of the centre line represent the same level of fitness. However, the fitness level on the left is obtained using less training than the point on the right. Put another way, you may perform as well training 10 hours per week as you would training 14.

That might be great in theory, but how can it be applied? We’ll I’m glad you asked. Firstly, instead of training as much as you possible, I believe riders should aim for a training load that optimizes their performance. I understand that it is hard to resist the more is better theory, but I also believe that many riders with unstructured training reside on the decline side of the performance bell curve and would benefit from a permanent (or at least longer term) decrease in training load.

If you are going to optimize your training, you will require some quantifiable measures, that means recording your training and performance. Fortunately, programs like Strava Premium and Training Peaks enable this to be done relatively easily.

To baseline your performance, you can use a test like a time trial, FTP test, hill climb or regular race as a reference. Increasing or decreasing your training load in a controlled and measurable way can be done by tracking your weekly TSS, Training Load or Suffer Score.

If you increase your training load 10% for a few weeks, how do you perform? If you decrease your training load 10% how do you perform? Importantly, how do you feel? How is your overall energy? How is your sleep? Are you happier having more time for family and friends?

Importantly, if you are using Strava’s Fitness and Freshness chart or Training Peaks' Performance Management Chart, a drop in training load will lead to a drop in Fitness or CTL. And competitive athletes do not like to see graphs that say their fitness is decreasing!

However, there is another source of quantitative evidence that may suggest things aren't so bad. If you also monitor your power curve, you may find that your performance is actually improving, even though the program considers you to be less fit. This is what happens in a taper, where an athlete decreases training and sacrifices a small amount of fitness, knowing it will result in an increase in performance.

As a coach, this is a mental hurdle that I often need my riders to overcome. Yes, some people do need to train more to reach their full potential, but there are also many who perform better while training less. However, they first need to come to terms with their fear of losing fitness and shift their mindset to maximising performance.

Fortunately, by the time someone seeks the assistance of a coach, they have already come to the realization that there are probably more effective ways of training and are generally more open to having their thinking challenged. However, I believe there is still a large number, even a majority of riders not reaching their potential because they are still mentally wedded to a linear model of performance.